Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED) is an innovative approach to reducing crime by thoughtfully designing and managing the built environment. By altering physical spaces in strategic ways, CPTED aims to make criminal activity less appealing or feasible while increasing community safety and cohesion.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore CPTED’s origins, principles, real-world applications, and benefits — along with expert resources to deepen your understanding.

What is Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED)?

CPTED is a multidisciplinary strategy that combines principles of criminology, urban design, architecture, and landscape planning to reduce crime and enhance public safety. The underlying theory is that a well-designed environment can influence human behavior positively and reduce the opportunity for crime.

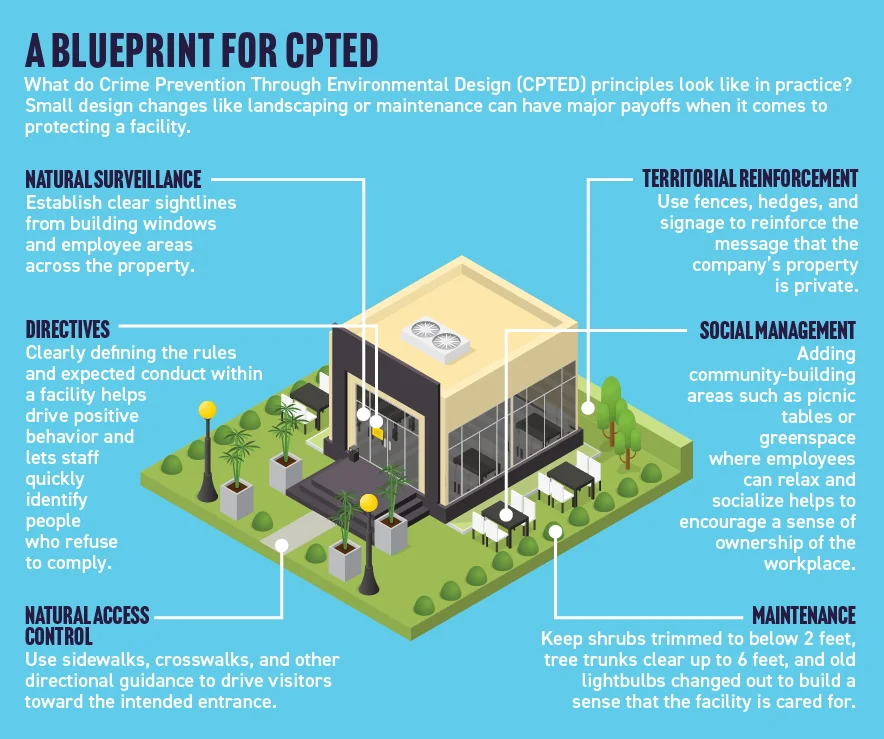

According to the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, CPTED focuses on designing the physical environment in ways that deter crime through:

This approach empowers communities and property owners to take proactive measures that improve security without relying solely on law enforcement or technology.

Historical Background and Evolution of CPTED

The concept of using environmental design to prevent crime dates back centuries, but the formal CPTED framework emerged in the 1970s.

C. Ray Jeffery, a criminologist, first coined the term “Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design” in his 1971 book, emphasizing environmental psychology’s role in crime deterrence.

Oscar Newman’s Defensible Space Theory (1972) introduced ideas about designing housing and public spaces to foster ownership and natural surveillance.

Since then, CPTED has evolved, incorporating community participation, technology, and environmental psychology to create safer, more vibrant urban environments.

For a deeper dive into CPTED history, the National Institute of Justice provides a detailed overview.

The Four Pillars of CPTED: Detailed Explanation

1. Natural Surveillance

Natural surveillance means designing environments to maximize visibility and increase the chances that offenders will be seen. This can be achieved by:

Installing adequate lighting in streets, parking lots, and pathways. The Illuminating Engineering Society provides standards for effective lighting.

Using low or transparent fencing and landscaping that does not create hiding spots.

Positioning windows and entrances so occupants can observe street activity and public spaces.

Studies show that areas with increased natural surveillance experience significantly fewer crimes, especially property crimes and vandalism (CPTED Journal, 2018).

2. Natural Access Control

This principle involves guiding people entering and exiting a property by strategically placing entrances, exits, fencing, and landscaping to reduce access points for potential offenders.

Examples include:

Using walkways and gates to direct visitors past reception areas or security checkpoints.

Installing physical barriers such as bollards or planters to restrict vehicle access.

Designing parking lots to funnel foot traffic through monitored zones.

The Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design Training Manual by Campbell County Wyoming offers practical implementation tips.

3. Territorial Reinforcement

Territorial reinforcement creates a sense of ownership and responsibility for a space by clearly defining private, semi-private, and public areas.

Methods include:

Using signage, fences, and landscaping to delineate property boundaries.

Incorporating design features such as patios, porches, or decorative pavement to signal “ownership.”

Encouraging community involvement and stewardship programs.

When residents or businesses feel a strong territorial connection, they’re more likely to report suspicious activity and maintain their spaces, discouraging criminals.

4. Maintenance and Activity Support

CPTED emphasizes the importance of ongoing maintenance and encouraging legitimate activities in public spaces to deter crime.

Proper upkeep signals that an area is monitored and cared for, reducing vandalism and neglect (known as the “Broken Windows” theory).

Hosting community events or activities increases foot traffic and natural surveillance, further deterring crime.

For more on this, see The National Crime Prevention Council’s insights on maintenance.

How CPTED is Applied in Different Settings

Residential Areas

In neighborhoods, CPTED strategies might involve:

Keeping shrubs and trees trimmed to eliminate hiding spots.

Installing streetlights in dark or poorly lit areas.

Using fences that define property without blocking sightlines.

Encouraging neighborhood watch programs.

The National Association of Realtors highlights CPTED’s role in community safety initiatives.

Commercial Properties

Businesses benefit from CPTED by:

Designing entrances and exits to improve control and surveillance.

Using glass walls and windows for visibility of parking areas and storage spaces.

Installing lighting that reduces shadows and dark corners.

The International CPTED Association offers case studies on retail and commercial CPTED success stories.

Public Spaces and Parks

Urban planners use CPTED in parks and public spaces to:

Place seating and playgrounds in visible locations.

Create well-lit, direct pathways.

Design landscaping that doesn’t obscure sightlines.

The Project for Public Spaces provides excellent resources on designing safer public places.

Benefits of Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design

Reduced Crime and Fear of Crime: Studies show CPTED reduces property crime, vandalism, and even violent crime in some cases.

Stronger Community Cohesion: Well-designed environments foster social interaction and pride.

Economic Growth: Safer neighborhoods attract businesses and residents, improving property values.

Sustainability: CPTED encourages smart, cost-effective urban planning with long-term benefits.

Challenges and Limitations

While CPTED is powerful, it’s not a standalone solution. Challenges include:

Balancing security with accessibility and aesthetics. Over-securing spaces can feel oppressive.

Adapting CPTED principles to diverse urban environments requires customization.

Ongoing maintenance and community involvement are essential for success.

For a detailed critique, see The Urban Institute’s evaluation of CPTED.

Emerging Trends in CPTED

New technologies and social strategies are enhancing CPTED effectiveness:

Smart lighting and IoT sensors that adjust brightness based on activity.

Community engagement apps to report issues quickly.

Integration with public health and sustainability efforts to create holistic urban environments.

Conclusion

Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design offers a proactive, evidence-based framework for making our communities safer through smarter design. By understanding and applying CPTED principles, architects, planners, law enforcement, and residents can collaborate to create spaces that naturally deter crime and promote well-being.

Further Reading and Resources